The Book of Books: What Literature Owes the Bible

By MARILYNNE ROBINSON

Published: December 22, 2011

This is, as if out of the blue, the best article and commentary on literature I've seen recently, about the significance writing invests in the complexities of daily life. The question of why do we write, and finding a satisfactory answer, has been around a long time, apparent in the Good Book, both in its age and its form. The logic takes us in a certain direction, and here you'll find a fascinating discussion of Christ's assumption of the role of 'the least of these' to show, in short, the reality behind experience.

And given the nostalgia commonly experienced at this time of year, it seems timely to be reminded of Dostoevsky's The Idiot and Faulkner's Benjy.

We could take this article and run with it in many directions, as far as exploring the Christian persona as it applies to writing. Perhaps, the thought might occur, a writer must be humble, something of 'an idiot' to not be blinded by what a society might see as so important, in order to gain a broader vision of reality. To the ends of larger understandings a writer is after, being humble could be a good clean mental habit. (Can that habit be divorced from the general living of life, is one question.)

There is something of the obscure idiot in the lives of many great writers. Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Chekhov, Larkin... more recently D.F. Wallace. The fool is special to Shakespeare. It's as if in order to do the work you have to think completely differently, and that can only be an individual discovery, the bubbling-up of a great intuitive thing, something that doesn't pay off in the short term or in the immediate or in any practical estimation of the world's workings. But from such a quality, an overriding deep sensitivity, an ability to be somewhat Buddha or Christ-like, which normally might bring silence.

The writer is great for his ability to touch that particular creature of particular tastes and temperament, the human being. (Kerouac had that gift, before his own defense mechanisms got him.)

Modern life, of course, requires constant choice-making. It comes at you fast. The clock is ticking, unless you master some ability to refrain, for a time suspending somehow all the extra needs.

And so, the writer's position is a difficult one. How does he maintain a life when he is intuitively distanced from so much that is practical existence, as he is simply in a mode of being elsewhere?

Yes, the idiot... he makes no reaction to something like people normally react. He sits and thinks on his own, as if he weren't a part of time. What language does he have to share his deeper moment with anyone beyond the quick sketch of St. Francis who abhorred money and spoke to creatures? Joyce's, maybe, who took all that dullard rote Catholicism and transformed it into a rich and beautiful examination of the reality of a moment. What chance does an American, wrapped in the shallow but endless cover of the great Now of current style and habit so commonly clung to, have to escape so as just to think a little differently and independently? Each time he does refrain from joining in, it's as if he's using up a finite reserve of ammo, raising the possibility each time that he will be thought of commonly as an idiot.

Sometimes he finds himself gaining in strength from his independence. Sometimes he finds strength, greatly so, from finding older longer traditions or things to do that support a general creativity. He will both like and dislike the time he gets by himself on his own for the work he sees as important. He won't have all the energy he wants, but he will try.

Any writer we know, I get the sense, they just kept at it. Each moment of free time was a moment of Now to take advantage of.

Post Script:

I sometimes wonder, why would we read anything but the Good Book. It's got everything in it. In a way, it's all we need. Does that sound strange to the modern ear? Probably. "We've already read about Job, what else are we going to get out of it?" "Me, I'd rather read about Richard Holbrooke's efforts of diplomacy, or about bio-fuel, or about the economy, the educational system, etc., etc." Or, "why read Faulkner, but out of some exploration of literary technique, though, of course, this business about Benjy being a sort of Christ Stand-In is sort of interesting."

Well, to read the Bible, or something that touches the same issues, invites us toward a broader frame on reality. What is reality? How should we treat the world? Maybe the business about the gentle Lamb of God turns out to be a practical way to go through life after all, even though initially it seems way too passive. Maybe there are deeper things to think about, in a way that is beneficial to our lives and the human condition here, ways to live that we haven't explored so well in our rush to go about 'taking care of things.'

But why read, say Hemingway, when we could be reading Corinthians? Maybe because, to attempt to seriously answer the question, there is buried within it a form of spiritual awakening, a revelation of 'here's what this particular writer's mode of consciousness allows one to see, better than might be, pointing out maybe the particular limitations of such thought so that we can do a little bit better, all part of a great experiment.'

It is interesting that the passive idiot type recurs in literature, or at least the figure of someone walking the line between what seems practical or is allowed by society (like a camping trip conducted in a certain practical way) and the ultimate mysteries that come before him (like the great silence that opens up after all the matters of camping and fishing for dinner are taken care of, bringing a spiritual moment.) Is Nick, the camper in the famous Hemingway story, just a guy with a bit of stress disorder seeking calm in the woods?

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Monday, December 19, 2011

Such a gloom Christmas time can bring.

Left alone, one's thoughts become a weary rut, as if not quite gone over a million enough times. Like 'the time I became a loser.'

Went back for my first homecoming. I started out in my old VW Rabbit, but the cylinder head was slowly giving way and the best pressure the cylinders could push was about 45 mph and that was probably going downhill. Not a safe speed for the Thruway. I made it from Westmoreland to the Utica exit. Nursed the thing home to my dad's apartment. He let me borrow his car. That night I called her, the girl I'd courted for a bit more than a year. I had graduated, she was a junior now. I called her up. It didn't last long. "Who's this," she demanded. I tried to explain myself, got cut off. "Ha ha," I said, as she dismissed me.

And so I went to the football game the next day. And all the 'no's of the previous year seem to weigh in on my, even in the bright fall sunlight in one of the beautiful happy places of earth. I saw her walk by as I caught up briefly with a guy about what was going on. And then I walked off in the opposite direction, toward the end of the playing field, not looking back. "One more word and I'll go the dean and charge you with..." that kind of a thing. Not a lot of positive. A lot of stilted conversations. And so I walked down to the end of the football field, to think about it, to stew, to not be happy.

Well, my friends were around. I hadn't seen them in a long time. Two of my closest friends wanted a little puff of doobie so I went off with them. And when I came back, there she was, sitting by herself, on the grass, her legs tucked up. I'd been told by a by a kid I knew in her class that her friends, who had never been at all nice to me, say that I had 'been her boyfriend.' And I said to myself, stung as I was, 'yeah, right.' And so I stood there as she sat there.

I guess I was about to go and say something to her just as about as she stood up. I looked down and dragged my toe through the cinder fine grint of the running track in that classic more of shyness. And she walked past me and away.

And so it's me, you know, who screwed it all up in the end, who was an asshole, who was too pessimistic (a Capricorn.) It's me who did the worst possible thing, me who is responsible for not being open, and for worse, for dashing a relationship between possible soul mates in the trash and ruined in an instant whatever might have come out of it, happy times of adventure, a wedding for family members, happy kids, happy grandparents, even as it would have been a struggle. But no, none of that transpired, that nice meet in college kind of a thing that is so appropriate. The rest I'd rather not talk about.

So that is one person's Christmas gloom, a chasm of grief to buy and hold onto, a fine holiday bitterness, no one's fault, but your own, never to be right again, too many years gone by.

Maybe by writing it, there will be some abatement, some counter swing of a pendulum, that gloom will lift, that the day of Christmas will offer some form of peace and hope.

Left alone, one's thoughts become a weary rut, as if not quite gone over a million enough times. Like 'the time I became a loser.'

Went back for my first homecoming. I started out in my old VW Rabbit, but the cylinder head was slowly giving way and the best pressure the cylinders could push was about 45 mph and that was probably going downhill. Not a safe speed for the Thruway. I made it from Westmoreland to the Utica exit. Nursed the thing home to my dad's apartment. He let me borrow his car. That night I called her, the girl I'd courted for a bit more than a year. I had graduated, she was a junior now. I called her up. It didn't last long. "Who's this," she demanded. I tried to explain myself, got cut off. "Ha ha," I said, as she dismissed me.

And so I went to the football game the next day. And all the 'no's of the previous year seem to weigh in on my, even in the bright fall sunlight in one of the beautiful happy places of earth. I saw her walk by as I caught up briefly with a guy about what was going on. And then I walked off in the opposite direction, toward the end of the playing field, not looking back. "One more word and I'll go the dean and charge you with..." that kind of a thing. Not a lot of positive. A lot of stilted conversations. And so I walked down to the end of the football field, to think about it, to stew, to not be happy.

Well, my friends were around. I hadn't seen them in a long time. Two of my closest friends wanted a little puff of doobie so I went off with them. And when I came back, there she was, sitting by herself, on the grass, her legs tucked up. I'd been told by a by a kid I knew in her class that her friends, who had never been at all nice to me, say that I had 'been her boyfriend.' And I said to myself, stung as I was, 'yeah, right.' And so I stood there as she sat there.

I guess I was about to go and say something to her just as about as she stood up. I looked down and dragged my toe through the cinder fine grint of the running track in that classic more of shyness. And she walked past me and away.

And so it's me, you know, who screwed it all up in the end, who was an asshole, who was too pessimistic (a Capricorn.) It's me who did the worst possible thing, me who is responsible for not being open, and for worse, for dashing a relationship between possible soul mates in the trash and ruined in an instant whatever might have come out of it, happy times of adventure, a wedding for family members, happy kids, happy grandparents, even as it would have been a struggle. But no, none of that transpired, that nice meet in college kind of a thing that is so appropriate. The rest I'd rather not talk about.

So that is one person's Christmas gloom, a chasm of grief to buy and hold onto, a fine holiday bitterness, no one's fault, but your own, never to be right again, too many years gone by.

Maybe by writing it, there will be some abatement, some counter swing of a pendulum, that gloom will lift, that the day of Christmas will offer some form of peace and hope.

Monday, December 12, 2011

Then it occurs to me, President Kennedy wanted for us to admit our pain, the pain of being human in this small world that we share. Something he never did in public, the severe physical pain he had.

For the last twenty five years or so I have woken up in one form or another of depression. It varies somewhat. It's not like that of the woman in our town who would walk along College Street in an almost zombie-like medicated state (purportedly she had witnessed something horrible), it's not like I don't function, but it's there on a daily basis. There have been ups and downs as far as days one wants to get up out of bed, days one finds not much reason, maybe just needs rest, lots of rest. I'm probably not that different from a lot of people in that regard; maybe it's just that most people grow up and find some profession to go to during the day, which more or less takes care of things. The fault is mine for the job of working nights, leaving the hours before to stew. (Is writing, just on your own, a job of any sort, one that offers great promise or security?)

I've tried homeopathic stuff, holy basil, GABA, supplements like B vitamins, amino acid tyrosine, L-arginine, 5-HTP. (Along with a fair amount of natural anti-inflammatory herbals like astragalus and Chinese skullcap.) Who knows, sometimes I feel they help, kind of pull away the curtains so that daylight can flow in and out up there, a sense of well-being. Yes, sometimes I could almost swear they help. To find some glimmer of happy childhood, before the morose Irishman, before things like regrets. Of course, this is why we must exercise, yoga, an hour of something aerobic, just to get yourself back in a decent mood. Maybe it's just that for the great percentage of our evolution we walked constantly, always doing something physical, carrying in our hands a reassuring bow and arrow or a spear, or doing something with an axe. And perhaps, maybe most therapeutic of all, words, the writing down of things, the steady 'showing up' to pick up the worded thoughts of a previous day, dust them off, shine them, and then continue with the train of thought.

So you get up out of bed. Leave the curtains open at night, just to get some light to help you get going. Things like dirty dishes in a sink are very heavy. Hard even to make the tea, but you can, and finally do, and stuff like this, small accomplishments, help you not have a poisoned brain toward the day. We're social animals. It helps to get out of the apartment. This is why there are coffee shops, to let one's own brain waves mingle in the electric flows of people who have already started their day, already working on something. But sometimes I find them too noisy, distracting, too much of an effort, and that the best approach to them is that of a birds, like the sparrows one finds on the terrace outside, to find a little comfortable perch in the sun.

When you are depressed you can fall to that foolish thing called living in the past. There are the ninja armies of should'a, would'a, could'a, leaping out at you unannounced, a particular memory, options not taken, gracious efforts not made in your stung shyness that was already prone to 'the artistic high-strung temperament' already even back then, as if you didn't have your eyes open to the beauty of life before you. Things of your youth you feel bad about in middle age. You'd like to, as they say, seize the day, but of course, you can't.

Our college wants us to write a little blurb about what we've been up to as we go to our 25th reunion. Maybe that too, besides praying to President Kennedy, prompts these thoughts. What have I done... Well, basically I've been a barman. I've worked in two establishments, neighborhood places, but places well-known, well-respected enough to get flow from a good portion of the town. I get up, get ready, and then I go in, get the bar ready, get set-up, the door opens, and then I'm solicitous for the next hours, etc. I've conversed with many people, with many on a regular basis. I've served some function in the town, and been there steadily, on Wisconsin Avenue, waiting on whoever walks in the door (with some exceptions) for a good amount of time. Not showy enough to be a legend, but maybe a guy who's generous as long as he can stand it.

Something to mention, but not a huge amount to crow about. I'll mention too that I worked on one project steadily, thus the novel, self-published. I try not to talk too much about it at work, the 'what else do you do besides tend bar (because obviously you are intelligent),' oh, I wrote a novel, it's kind of like The Catcher in the Rye... boy meets girl, boy fucks it up, repeatedly, blah blah, what the hell is it about anyway, I don't know, I just wrote the damn thing, I guess it's like this modern take on Hamlet, as if we were to drop into a college setting, but not the court intrigue plot level, no nothing like that, basically about as readable and publishable as Joyce, later Joyce... Gloomy crap no one needs to read, and look here I am staring at my naval again talking about it and don't we have anything better to talk about and hey how's your wine working with whatever . Whatever.

But I say all this because we all our brave, what we do, how we live and face life, knowing an inkling of what ultimately will happen to us. I say this knowing that we all have regrets. And ultimately we all must find some faith in the notion that the world is, as it were, our soul mate, that therefore we love the world, that we trust the world implicitly, even knowing that in doing so we open ourselves up to pain. Maybe that is a reason, yet another one, why we forgive, forgive another as one who just like us has walked out onto the ice in hopes of finding.

I have no doubts in my mind that Lincoln suffered from the gloom, fought to live through it, to find a way 'out' as it were, to find a satisfying solution, a connection, to a great puzzle to put his foot upon, to find a meaning to 'dedicate' his own life to. Perhaps he was lucky to find such a role, though all the issues he would then face each presented itself with the problem of depression in various states of scale, and to not just sit there feeling helpless, lost.

One day, I vaguely remember, we saw the woman walking along College Street, and she looked surprisingly normal, as if something had blown away, and she was taking one step at a time and taking care of things. She had her life back, if not all those lost years.

Postscript, the usual after-thoughts that pile in: There is a part of the mind, the thinking artistic mind that, perhaps because of its highness, leaves one gentle to the point of passivity. The artist can't help the mode, passive to the truth, and this habit tends to place him at odds, to some extent, with any society she/he falls into, which does not encourage passivity because all must have rules to follow, to take a place in the pecking order. The vehicle by which he/she takes in that which shall be reformed and recreated as art seems to cause him to fight less than he should for the life he wants and the things even his heart cries out for. Sad on both ends, witnessing the sufferings of others, like the busboy with family and children far away, not seen in years, unable to help, realizing life must therefore be a self-minded battle, sad for not being as pro-active as he should be for his own.

For the last twenty five years or so I have woken up in one form or another of depression. It varies somewhat. It's not like that of the woman in our town who would walk along College Street in an almost zombie-like medicated state (purportedly she had witnessed something horrible), it's not like I don't function, but it's there on a daily basis. There have been ups and downs as far as days one wants to get up out of bed, days one finds not much reason, maybe just needs rest, lots of rest. I'm probably not that different from a lot of people in that regard; maybe it's just that most people grow up and find some profession to go to during the day, which more or less takes care of things. The fault is mine for the job of working nights, leaving the hours before to stew. (Is writing, just on your own, a job of any sort, one that offers great promise or security?)

I've tried homeopathic stuff, holy basil, GABA, supplements like B vitamins, amino acid tyrosine, L-arginine, 5-HTP. (Along with a fair amount of natural anti-inflammatory herbals like astragalus and Chinese skullcap.) Who knows, sometimes I feel they help, kind of pull away the curtains so that daylight can flow in and out up there, a sense of well-being. Yes, sometimes I could almost swear they help. To find some glimmer of happy childhood, before the morose Irishman, before things like regrets. Of course, this is why we must exercise, yoga, an hour of something aerobic, just to get yourself back in a decent mood. Maybe it's just that for the great percentage of our evolution we walked constantly, always doing something physical, carrying in our hands a reassuring bow and arrow or a spear, or doing something with an axe. And perhaps, maybe most therapeutic of all, words, the writing down of things, the steady 'showing up' to pick up the worded thoughts of a previous day, dust them off, shine them, and then continue with the train of thought.

So you get up out of bed. Leave the curtains open at night, just to get some light to help you get going. Things like dirty dishes in a sink are very heavy. Hard even to make the tea, but you can, and finally do, and stuff like this, small accomplishments, help you not have a poisoned brain toward the day. We're social animals. It helps to get out of the apartment. This is why there are coffee shops, to let one's own brain waves mingle in the electric flows of people who have already started their day, already working on something. But sometimes I find them too noisy, distracting, too much of an effort, and that the best approach to them is that of a birds, like the sparrows one finds on the terrace outside, to find a little comfortable perch in the sun.

When you are depressed you can fall to that foolish thing called living in the past. There are the ninja armies of should'a, would'a, could'a, leaping out at you unannounced, a particular memory, options not taken, gracious efforts not made in your stung shyness that was already prone to 'the artistic high-strung temperament' already even back then, as if you didn't have your eyes open to the beauty of life before you. Things of your youth you feel bad about in middle age. You'd like to, as they say, seize the day, but of course, you can't.

Our college wants us to write a little blurb about what we've been up to as we go to our 25th reunion. Maybe that too, besides praying to President Kennedy, prompts these thoughts. What have I done... Well, basically I've been a barman. I've worked in two establishments, neighborhood places, but places well-known, well-respected enough to get flow from a good portion of the town. I get up, get ready, and then I go in, get the bar ready, get set-up, the door opens, and then I'm solicitous for the next hours, etc. I've conversed with many people, with many on a regular basis. I've served some function in the town, and been there steadily, on Wisconsin Avenue, waiting on whoever walks in the door (with some exceptions) for a good amount of time. Not showy enough to be a legend, but maybe a guy who's generous as long as he can stand it.

Something to mention, but not a huge amount to crow about. I'll mention too that I worked on one project steadily, thus the novel, self-published. I try not to talk too much about it at work, the 'what else do you do besides tend bar (because obviously you are intelligent),' oh, I wrote a novel, it's kind of like The Catcher in the Rye... boy meets girl, boy fucks it up, repeatedly, blah blah, what the hell is it about anyway, I don't know, I just wrote the damn thing, I guess it's like this modern take on Hamlet, as if we were to drop into a college setting, but not the court intrigue plot level, no nothing like that, basically about as readable and publishable as Joyce, later Joyce... Gloomy crap no one needs to read, and look here I am staring at my naval again talking about it and don't we have anything better to talk about and hey how's your wine working with whatever . Whatever.

But I say all this because we all our brave, what we do, how we live and face life, knowing an inkling of what ultimately will happen to us. I say this knowing that we all have regrets. And ultimately we all must find some faith in the notion that the world is, as it were, our soul mate, that therefore we love the world, that we trust the world implicitly, even knowing that in doing so we open ourselves up to pain. Maybe that is a reason, yet another one, why we forgive, forgive another as one who just like us has walked out onto the ice in hopes of finding.

I have no doubts in my mind that Lincoln suffered from the gloom, fought to live through it, to find a way 'out' as it were, to find a satisfying solution, a connection, to a great puzzle to put his foot upon, to find a meaning to 'dedicate' his own life to. Perhaps he was lucky to find such a role, though all the issues he would then face each presented itself with the problem of depression in various states of scale, and to not just sit there feeling helpless, lost.

One day, I vaguely remember, we saw the woman walking along College Street, and she looked surprisingly normal, as if something had blown away, and she was taking one step at a time and taking care of things. She had her life back, if not all those lost years.

Postscript, the usual after-thoughts that pile in: There is a part of the mind, the thinking artistic mind that, perhaps because of its highness, leaves one gentle to the point of passivity. The artist can't help the mode, passive to the truth, and this habit tends to place him at odds, to some extent, with any society she/he falls into, which does not encourage passivity because all must have rules to follow, to take a place in the pecking order. The vehicle by which he/she takes in that which shall be reformed and recreated as art seems to cause him to fight less than he should for the life he wants and the things even his heart cries out for. Sad on both ends, witnessing the sufferings of others, like the busboy with family and children far away, not seen in years, unable to help, realizing life must therefore be a self-minded battle, sad for not being as pro-active as he should be for his own.

Saturday, December 10, 2011

Hic Iacet Arthurus, Rex Quondam Rexque Futurus

Christmas shopping... I think I'd rather be reading Finnegan's Wake. Not an easy time for an attempted writer, feeling the obligation to find decent presents for everyone. You can only imagine how Ernest H. felt when he couldn't write anymore, mumbling to himself, turning previously written pages. Get out of the house. Go to some little coffee shop, just to be away from the desire to organize. Sit in a sunny spot, write a letter to an old professor of mine. (Sent hi a copy of my book, never got back to me.) Satisfied, a little bit, I go looking for guitar strings, and maybe a Shake Shack hamburger. Guitar Shop is closed, done. (I have a feeling they brought it on themselves from what people tell me about the experience there, but hard times for a mom & pop brick and mortar.) Hamburger okay, no epiphany. Didn't eat the bun anyway.

The greening bronze dome of Saint Matthew's rises above all the interesting people walking by on Connecticut Avenue excited that it's Friday in the cold mid-afternoon twilight. Women walking awkwardly on heels stepping along the pavement. Many people hip. Cars. A "GOING OUT OF BUSINESS, 50% off, everything must go" Filene's Basement placard spotted above M Street. Hmm, should a ragamuffin like me try to find something decent to wear, not really able to face the notion of serious Christmas present shopping? Feel like a creep, but also a flowing empathy for everyone, their faces, their shoes, their burdens... some people you take a liking to, though you don't need to know them... It's as if you had the sympathy of God for all them.

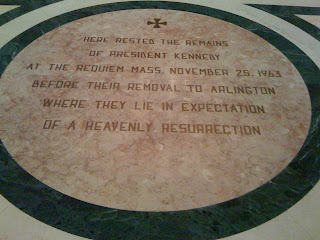

I head off to St. Matthew's. Which I'm a bit shy about. Fresh from the doom of writing in a notebook about events that didn't augur well, just a mood, I have a need to go see that spot where President Kennedy's casket rested in the great church, lain, after he was slain. I have need of a prayer and a brief cathartic gush of mourning for someone who knew the burden of pain, who loved life and the world enough to think about the deeper meaning of reality behind daily events, something my father thought worthy, something John F. Kennedy grew into, the light by which he inspired us then and to this day. The past is the past. You may want to change parts of it, but you can't, and there are good and great things about current reality, but there also are things that haunt you like ghosts. And you need a sort of talisman, a prayer, a mandala, to protect you, or else such things can eat at you. You wish them to go away, but they say things to you. You try not to spiral. Walk, do yoga, ride a bike, whatever it takes.

Entering through a side door, the one Pani Korbonska liked to enter through, one found four or five people praying in silence, either before lit candle, or facing the altar, a low soft hum from them. One woman sitting upright, staring ahead without emotion, taking a break. Gregorian chants playing quietly in the background, sounding live acoustically, but invisible. No vacuuming going on, though afternoon in-between masses vacuuming is not an unpleasant sound in a cathedral somehow, as if integrally related to the swinging of smoky incense, just its opposite, as if one had to carefully gather holy dust and scent back up again, recycling it, as it were. Three o'clock, on a Friday... The last time I was down here was to buy a black tie and a white shirt from Brooks Brothers for my father's memorial service. Music in background. Heavily curtained confessional booth. Serious prayer going on for a few. I dip my hand in the water, do a cross yourself thing, make a little bow, take a right, then a left, into the main aisle.

Walk up the carpet, to the edge, the marble's beginning before the main altar. A round inlay on the floor. ... The Mortal Remains of President Kennedy... I approach it, having bowed, slipped my courier bag into a pew (number 3, on the right), and now, now it's time for a prayer, one you've felt you've wanted to say for a long time, maybe since you were a kid. Gentle knight. Take a picture, read the words, look, the little cross inlay. It was here. Here, though hard to imagine the casket, moreso the swirling atomic dust of the living man frozen for a little while as the soul had left it still in form, and the soul present somehow, as if to say, 'this was finally me and all my works for you.' Bow down, on one knee, and one puts a hand down on the marble, just at the front edge of this circle inlayed. Amidst all the "Oh, No's" of life, you were a kid, you listened to his speeches, a record in the college library, many times, over again, that calling voice, comforting, telling us the meaning of life and what we should do, yeah, sometimes coached in and heavy with political and Cold War era terms, but often a good deal deeper than that. Yes.

Paw-like hand gently touching the marble, and no one saying, no you can't do that, just a fine moment of prayer coming up and down through fingertips, "President Kennedy, thank you and please show me, if you have any wise advice, the way for here I am and I have tried and feel I need to pray to you, for I have things that I'd like to redo in the past, and maybe I am not so sure of what I am doing here and now, but here I am comforted by you and by all you did and your words, which I am indebted to." Or maybe I was telling him of my father's passing, or of some sorrow or of some question, finding within a guide for life. "Jack. Show me the way, the right thing to do, and what this writer should do with himself." While trying to keep it on the light side, because he had such a good sense of humor.

A meditation in the pew, looking over at the spot. Kneel for a prayer. A prayer to my Dad. Then, to the chapel of St. Francis, mosaic inlay, green happy rolling Tuscan hills, animals and birds, waters, distant hill towns with glints of gold, blue sky, fowl of the air. Another prayer, kneeling, and then, it begins to wear off and one must quietly exit and allow other people their little real prayer time before more church business comes. Softly out through the side door.

Then feeling some dim obligation to go shopping, I enter the doors of Filene's Basement, already teeming at four o'clock, workers looking for bargains, long lines at cash register. Upstairs to Men's. Find a suit, charcoal black, 40 regular, seems to fit, though I look like a bum what I've put on today, my hair. "She wanted you to be a gentleman afterward, not before," a friend's words ring. "Treat a duchess like a whore, and a whore like a duchess," it reads, some saying somewhere in one of the JFK biographies. Shopping obligation, not shopping therapy. President Kennedy wore suits. My Dad too. Maybe a suit will help, help me find some golden inner guidance. Put on jacket, look in mirror. Futz over to the fitting room. Pay something like $105 for the suit. Then go look at shoes. some shopper I am, but I find a few pairs, maybe for work, left foot hurting, Chuck Taylor and pavement causing a particular 'what are you doing with your life' kind of pain in the ball of the foot that you can't even limp to sooth. Maybe it's about time I got some better shoes for work.

Then it's a quiet night. The kind you order Chinese food delivery and don't want to talk to anyone, but maybe clean the house a little, before the shopping, still deeply disturbing at this point, in earnest must commence.

Thursday, December 8, 2011

General Wine Thoughts

When I first came to tend bar at a French bistrot some seven years ago I really didn't know too much about wine, other than that it tasted good and that there was alcohol in it, allowing for the famous mildly euphoric and relaxing effect. I don't suppose it took long for a rudimentary understanding of French wines, Bordeaux being blends of Cabernet and Merlot, Red Burgandies being Pinot Noir, the Southern Rhone and Languedoc wines being of Grenache and Syrah along with a few other varietals, and then along with a whole range of minor exceptions, varieties, particular wines unique to certain areas, all alike but different. I'd ask my guys, long experienced drinkers of French wines, what's this Faugeres, or what's a Bandol, or a Madiran, I mean, as far as being able to explain it to people. And typically the cat would reply, 'oh, lovely wine, inky, spice...' and then go about his business.

The more you know about wine, the less it seems. Of course there are a whole range of intimidating titles, sommelier, second level, master of wine, and there are people who without being told can take a sip and tell you the particular wine it is, maybe even the chateau, and probably, the year. Jesus Christ. Yeah, I can roll wine over my tongue and make that slurp sound. I have a nose, though it's not always as clear as I'd like it to be. It is good, I'll tell you, to take your time. You might as well study the appearance of the wine, and then, after swirling the wine in a glass, you must give it a long good nose, which is basically the same as tasting the wine, but with some obvious difference, your tongue being the tactile part of your nose.

Now, humanity has evolved over a very long time from fish-like creatures. We have senses of sight, smell and taste for very good reasons, for having kept us alive and happy for so long. Our brains give us constant feedback, just as our guts do, though with guts usually there is some lag time, some delay, before you realize, hmm, maybe I shouldn't have eaten that. It is all these basic senses that we employ when we bring a glass of wine before us, and eventually with some intention of bringing that wine to match with something that we are going to eat. When you bring food and wine together, magic worlds of cuisine open up.

Noted wine writer Hugh Johnson makes an interesting point. The wine in your glass is water that has fallen from the sky, that has gone down into the earth, and then brought up through roots, then up the stalk of a grape vine and out to sustain the growth of the little budding grape which itself will hang there a whole season until it is perfectly ripe. Think of it! And so it comes to be that there is a mightily important concept that dovetails so neatly with French life. Terroir, the word is. And it refers to the locale where the grapes grow. It means this in the broadest sense. A wine's terroir, 'earth,' literally translated, is sun exposure, the slope, the type of soil, the kind of growing season, the weather, the kind of wine, the drainage of the soil; poetically used, terroir invokes, or evokes, basically all the living DNA that finds itself into all living things native to a region. There is the obvious suggestion that the grape is a very sensitive creature. Almost as if, if a Chinese restaurant delivery gu drove by a field of Pinot Noir often enough, you might get a hint of soy sauce in the air that touches the grape's skin.

Let's have an example of one kind of terroir. Let's take the South of France, maybe, oh, somewhere in the Languedoc. Say, Pic St. Loup, which is an interesting mesa-like mountainous formation that juts up from the hot plains near Montpellier, near Carcassone. Or perhaps a Corbieres, let's say. Down here, in this part of France, not to far away from Spain, we have what is called 'garrigue,' which means, 'dust,' more or less, but refers to all the wild aromatic herbs that grow there, happy in the sun, lavender, thyme, rosemary, sage. Just as we would in Provence, and in the Southern Rhone and in the Luberon. The roots up here on the slope have to reach way down to get their water and nutrients, bound to help produce a wine with minerally character, earthiness. And wine making itself is a natural process, after all. Just pick some ripe grapes, put them into a barrel, give them a crush and a stir, and the local yeast will come and enjoy a feast, in doing so, making wine out of grape juice. And even, in France, the wine maker, who takes the grape and juice and wine all through an aging process, is referred to as a 'vigneron,' a tender of the vines. And it is, indeed, in tending the vines where she or he succeeds. As they say, "God makes the wine. Just don't get in the way." If things are done right, if short-cuts aren't used, if grapes from a large area of varying stages of ripeness were thrown in together, necessitating some added chemical preservatives, if things aren't done stupidly, a wine comes out as it is meant to. A wine has character, just like a person or a dog, really. And this is a very good thing.

Now we come to food matching, or wine pairing, whatever you want to call it, ha ha. A wine that offers that taste and aroma of garrigue will go very well with a dish that has rosemary and thyme in it. It will work well with a dish that has black olive, caper, basil, garlic, the outer periphery of the garrigue neighborhood. The wild boar who has roamed through the scrub brush will eventually taste fine with a glass of such a wine.

I am reminded of the time the chef sat down at the bar to enjoy a plate of veal kidneys. Uhmm, he sort of grunted, when I asked him what sort of wine he might like. I was still learning, so I thought of rudimentary pairing guidelines, like maybe something peppery that generally works with red meat, like a Southern Rhone, or maybe a Bordeaux, for different reasons involving tannins. But the Chef shook his head, to say I should know better and that I had overlooked the basic element tying the dish together, a mustard sauce. And so, I was obliged to say "Duh" to myself, and go for a wine close to Dijon, the home of French mustard, which is a Burgandy, or, if had to, a wine from the Southern part of Burgandy, which is Beaujolais. It wasn't the red meat part, but the mustard, and the mustard itself worked well with the strong irony flavors of kidneys. In fact, the earth of the famous Cotes De Nuit, the Northern part of Burgandy's Cote D'Or, is irony stuff from the center of the Earth, whereas to the South it's ancient seabed limestone. (Now, I suppose a Madiran, which works well with liver, would have worked too, for the same iron red soil reasons, but that we didn't offer by the glass. ) And so Red Burgandy wines have an earthiness to them, even as they are on the lighter end as far as thickness in the mouth.

And that is yet another way how one learns the regional agreement as far as food and wine pairing. The dish of a particular area, a cassoulet, for instance, works perfectly with the wines of the region, as if everyone, God, chefs, tradition, and eaters, were in complete unspoken harmony.

Everything within the grape follows the timeline of maturity. Toward the end of the growing season, as the fruit is now ample and juicy, it is prone to being preyed upon by insect life, who cleverly are set on enjoying their own little share of the energy release of a long-ago Big Bang and the sunlight of a growing season. And so, naturally, the plant produces tannins, bitter darkening chemical compounds that work well to deter invasion and harm. These tannins are thought of, and treated carefully, so that a ripe grape is considered to also have not just ripe fruitiness but ripe tannins, that astringent quality that makes wine enjoyable in the mouth and quite obviously healthy as far as every sense of ours tells us. (Unless we find out the next day that the wine was a 'headache wine.')

And if balance has been achieved in the wonderful ripeness of fruit that has happened at the end of that long growing season, with the right amount of rain, a harvest time not too wet (to make the resultant juice flabby), nor too hot or whatever grapes don't really like, if all that year has gone well, then it stands, and often happens, that a wine has a beautiful balance, that the elements of its fruit, structure, acidity and tannins, mouthfeel and finish are harmonious to each other.

The more you know about wine, the less it seems. Of course there are a whole range of intimidating titles, sommelier, second level, master of wine, and there are people who without being told can take a sip and tell you the particular wine it is, maybe even the chateau, and probably, the year. Jesus Christ. Yeah, I can roll wine over my tongue and make that slurp sound. I have a nose, though it's not always as clear as I'd like it to be. It is good, I'll tell you, to take your time. You might as well study the appearance of the wine, and then, after swirling the wine in a glass, you must give it a long good nose, which is basically the same as tasting the wine, but with some obvious difference, your tongue being the tactile part of your nose.

Now, humanity has evolved over a very long time from fish-like creatures. We have senses of sight, smell and taste for very good reasons, for having kept us alive and happy for so long. Our brains give us constant feedback, just as our guts do, though with guts usually there is some lag time, some delay, before you realize, hmm, maybe I shouldn't have eaten that. It is all these basic senses that we employ when we bring a glass of wine before us, and eventually with some intention of bringing that wine to match with something that we are going to eat. When you bring food and wine together, magic worlds of cuisine open up.

Noted wine writer Hugh Johnson makes an interesting point. The wine in your glass is water that has fallen from the sky, that has gone down into the earth, and then brought up through roots, then up the stalk of a grape vine and out to sustain the growth of the little budding grape which itself will hang there a whole season until it is perfectly ripe. Think of it! And so it comes to be that there is a mightily important concept that dovetails so neatly with French life. Terroir, the word is. And it refers to the locale where the grapes grow. It means this in the broadest sense. A wine's terroir, 'earth,' literally translated, is sun exposure, the slope, the type of soil, the kind of growing season, the weather, the kind of wine, the drainage of the soil; poetically used, terroir invokes, or evokes, basically all the living DNA that finds itself into all living things native to a region. There is the obvious suggestion that the grape is a very sensitive creature. Almost as if, if a Chinese restaurant delivery gu drove by a field of Pinot Noir often enough, you might get a hint of soy sauce in the air that touches the grape's skin.

Let's have an example of one kind of terroir. Let's take the South of France, maybe, oh, somewhere in the Languedoc. Say, Pic St. Loup, which is an interesting mesa-like mountainous formation that juts up from the hot plains near Montpellier, near Carcassone. Or perhaps a Corbieres, let's say. Down here, in this part of France, not to far away from Spain, we have what is called 'garrigue,' which means, 'dust,' more or less, but refers to all the wild aromatic herbs that grow there, happy in the sun, lavender, thyme, rosemary, sage. Just as we would in Provence, and in the Southern Rhone and in the Luberon. The roots up here on the slope have to reach way down to get their water and nutrients, bound to help produce a wine with minerally character, earthiness. And wine making itself is a natural process, after all. Just pick some ripe grapes, put them into a barrel, give them a crush and a stir, and the local yeast will come and enjoy a feast, in doing so, making wine out of grape juice. And even, in France, the wine maker, who takes the grape and juice and wine all through an aging process, is referred to as a 'vigneron,' a tender of the vines. And it is, indeed, in tending the vines where she or he succeeds. As they say, "God makes the wine. Just don't get in the way." If things are done right, if short-cuts aren't used, if grapes from a large area of varying stages of ripeness were thrown in together, necessitating some added chemical preservatives, if things aren't done stupidly, a wine comes out as it is meant to. A wine has character, just like a person or a dog, really. And this is a very good thing.

Now we come to food matching, or wine pairing, whatever you want to call it, ha ha. A wine that offers that taste and aroma of garrigue will go very well with a dish that has rosemary and thyme in it. It will work well with a dish that has black olive, caper, basil, garlic, the outer periphery of the garrigue neighborhood. The wild boar who has roamed through the scrub brush will eventually taste fine with a glass of such a wine.

I am reminded of the time the chef sat down at the bar to enjoy a plate of veal kidneys. Uhmm, he sort of grunted, when I asked him what sort of wine he might like. I was still learning, so I thought of rudimentary pairing guidelines, like maybe something peppery that generally works with red meat, like a Southern Rhone, or maybe a Bordeaux, for different reasons involving tannins. But the Chef shook his head, to say I should know better and that I had overlooked the basic element tying the dish together, a mustard sauce. And so, I was obliged to say "Duh" to myself, and go for a wine close to Dijon, the home of French mustard, which is a Burgandy, or, if had to, a wine from the Southern part of Burgandy, which is Beaujolais. It wasn't the red meat part, but the mustard, and the mustard itself worked well with the strong irony flavors of kidneys. In fact, the earth of the famous Cotes De Nuit, the Northern part of Burgandy's Cote D'Or, is irony stuff from the center of the Earth, whereas to the South it's ancient seabed limestone. (Now, I suppose a Madiran, which works well with liver, would have worked too, for the same iron red soil reasons, but that we didn't offer by the glass. ) And so Red Burgandy wines have an earthiness to them, even as they are on the lighter end as far as thickness in the mouth.

And that is yet another way how one learns the regional agreement as far as food and wine pairing. The dish of a particular area, a cassoulet, for instance, works perfectly with the wines of the region, as if everyone, God, chefs, tradition, and eaters, were in complete unspoken harmony.

Everything within the grape follows the timeline of maturity. Toward the end of the growing season, as the fruit is now ample and juicy, it is prone to being preyed upon by insect life, who cleverly are set on enjoying their own little share of the energy release of a long-ago Big Bang and the sunlight of a growing season. And so, naturally, the plant produces tannins, bitter darkening chemical compounds that work well to deter invasion and harm. These tannins are thought of, and treated carefully, so that a ripe grape is considered to also have not just ripe fruitiness but ripe tannins, that astringent quality that makes wine enjoyable in the mouth and quite obviously healthy as far as every sense of ours tells us. (Unless we find out the next day that the wine was a 'headache wine.')

And if balance has been achieved in the wonderful ripeness of fruit that has happened at the end of that long growing season, with the right amount of rain, a harvest time not too wet (to make the resultant juice flabby), nor too hot or whatever grapes don't really like, if all that year has gone well, then it stands, and often happens, that a wine has a beautiful balance, that the elements of its fruit, structure, acidity and tannins, mouthfeel and finish are harmonious to each other.

Ulysses, one of the greats

The Modernists (maybe they would have preferred 'modernists'), they asked questions, like 'why make art,' 'what is art,' 'how do we perceive the things and objects that make up reality,' 'how does the artist's point of view effect the art,' 'what can we rightfully consider to be art,' and many more individual ones concerning their mediums and metiérs. The questions enlivened and inspired them, gave them raison d'etre and even firm ground to stand on. A miraculous period of art, often marked by boldness and also subtlety, portraying three-dimensional objects, landscapes, workings and inner ticking of the human mind, moods and mental states, modern life... and it all came out with clarity, if clarity was the proper thing for it.

Ulysses stands as a Modernist work, true to a bold and adventurous and innovative time. Joyce's use of stream of consciousness and repetition of a word through a passage was a big influence on Hemingway and the whole gang. Perhaps there is no better metaphor for what a book might be than that great book (which of course bows to the great epic ancient poem, itself one of the great examples of human literature.) It is a long book. It took a long time to write, as Joyce took progressively longer with each of his projects. (After all, things like that don't happen in a day.) There are many twists and turns, there is a lot of texture, and there is ever the question at the edge for the reader 'why write this, why read this,' while still reading it drop by drop.' The reader is entering the mind of someone, entering the flow of the words and thoughts. Is this heroic, both the effort and the slice of life portrayed? What is heroism? On every level a lot to sort through, and an overall lasting impression. The book is 'something.' It is a cultural milestone, a great achievement in history.

And perhaps along with that, there was (hopefully, is) a sense of a writer as someone giving us a grasp on reality and the passing of the days of life, the slices of moments of now that are both capturing the present moment but with the simultaneous ability to enjoy the past moments. It sounds like, or takes after, modern physics, quantum understandings. The sense of achievement we attach to such a work (even as so many thoughts are currently flowing through our heads as if a thousand Shakespeare characters were speaking their lines to us all at once) leaves us with a satisfaction of coming to an approximate guess about the big question, why do we write.

Anyone in the game these days has to ask the same question. Why write? How should we write? What is the intention? Do we write for any reason beyond the satisfaction it provides, the sense of calm? Do we do it for money, for fame and recognition, to which we must answer, obviously no, the mantle of humility ever attached to it. Writing comes from beyond us, after all, leaving us just the vessel of a day (like Ulysses' ship.)

MIlan Kundera recently posed the observing question, the issue of whether literature was destroying itself through the sheer overproduction of everyone, as indeed they are these days, writing a book, attempting to get it published. Somewhere in Le Rideau, The Curtain. It's a good point. Is it that everyone is Joyce?

I think it comes down to the condition that we are unable--in an odd way increasingly so, it seems--to recognize who and what is a great writer. Maybe that's selfish of me, an unknown. But I think it bears observing. Is it the 'publishable' work that brings us, typically, more than an experience of a particular set of issues told to us by an expert, a celebrity, a top academic who has mastered publishing the topical? We crave more than that. Is light captured if you understand it as a stream of particles, would be to ask a similar question about writers who have satisfied 'nailing something down.' Perhaps it is the 'unpublishable' stuff, the stuff that is too boring and plotless and amateur, that might better, through grasping the obscure and quiet reasons and guiding lights with no external concern other than to write, receive our general attention as not great marketing but great art. Like, for instance, Emily Dickinson, who couldn't be dragged out away from the house and her great understandings of all things, who wrote the immortal line, 'admiring bog.' (Of course, Joyce was 'published' through the help of Sylvia Beach, the ultimate generous art-house publisher patron.)

Joyce knew he was unpublishable in his great project. Fortunately Nora saved it from the fire. (One wonders, could he have come up with a more unpublishable book on so many levels and issues... Later, he tried actually.)

Having said my piece, I'll add, softly, that like Ulysses, and the hero himself, great art takes its own time. It would appear, perhaps, obsessive, foolish having nothing to do with the practical matters of worldly reality we human beings in society must live with and cope with. It has to include, perhaps softly at the edges, the great extent of the passing of time, 'a long time' in other words. (As Shane MacGowan observes in song.) And at the same time a sense of what time in the sense of moments to portray, is, that crazy thing, ever changing, ever slipping past us, ('bravely we beat on,' Fitzgerald wrote) that marvelous beautiful now we ever live in. How rich and rewarding life is, just as it is. That is all a great book needs to do. Like Keats' urn.

As an afterthought, a question: What has the digital age done to, or for, that moment of now? Our own now is peppered with now, other nows, but now qualified, sometimes real, as you can indeed share something real, even on facebook, with someone, but often muddled, overripe with illusory things of materialism, fame, with all the instant news we've developed a serious craving for, a lot of it pushing our own little real moments of now off to some exiled edge. Now gets corrupted, often enough, all too easily.

My sense is that if you were to wipe the slate clean from all the distractions, from all the diversions, you would find that the human being is an incredibly intelligent animal who is able to get some deep amazing stuff as far as thinking and considerations of what daily reality is. And you would find in the human the greatest faith in writing, just as Joyce must have had that unquestioning faith in writing as the thing to do.

Ulysses stands as a Modernist work, true to a bold and adventurous and innovative time. Joyce's use of stream of consciousness and repetition of a word through a passage was a big influence on Hemingway and the whole gang. Perhaps there is no better metaphor for what a book might be than that great book (which of course bows to the great epic ancient poem, itself one of the great examples of human literature.) It is a long book. It took a long time to write, as Joyce took progressively longer with each of his projects. (After all, things like that don't happen in a day.) There are many twists and turns, there is a lot of texture, and there is ever the question at the edge for the reader 'why write this, why read this,' while still reading it drop by drop.' The reader is entering the mind of someone, entering the flow of the words and thoughts. Is this heroic, both the effort and the slice of life portrayed? What is heroism? On every level a lot to sort through, and an overall lasting impression. The book is 'something.' It is a cultural milestone, a great achievement in history.

And perhaps along with that, there was (hopefully, is) a sense of a writer as someone giving us a grasp on reality and the passing of the days of life, the slices of moments of now that are both capturing the present moment but with the simultaneous ability to enjoy the past moments. It sounds like, or takes after, modern physics, quantum understandings. The sense of achievement we attach to such a work (even as so many thoughts are currently flowing through our heads as if a thousand Shakespeare characters were speaking their lines to us all at once) leaves us with a satisfaction of coming to an approximate guess about the big question, why do we write.

Anyone in the game these days has to ask the same question. Why write? How should we write? What is the intention? Do we write for any reason beyond the satisfaction it provides, the sense of calm? Do we do it for money, for fame and recognition, to which we must answer, obviously no, the mantle of humility ever attached to it. Writing comes from beyond us, after all, leaving us just the vessel of a day (like Ulysses' ship.)

MIlan Kundera recently posed the observing question, the issue of whether literature was destroying itself through the sheer overproduction of everyone, as indeed they are these days, writing a book, attempting to get it published. Somewhere in Le Rideau, The Curtain. It's a good point. Is it that everyone is Joyce?

I think it comes down to the condition that we are unable--in an odd way increasingly so, it seems--to recognize who and what is a great writer. Maybe that's selfish of me, an unknown. But I think it bears observing. Is it the 'publishable' work that brings us, typically, more than an experience of a particular set of issues told to us by an expert, a celebrity, a top academic who has mastered publishing the topical? We crave more than that. Is light captured if you understand it as a stream of particles, would be to ask a similar question about writers who have satisfied 'nailing something down.' Perhaps it is the 'unpublishable' stuff, the stuff that is too boring and plotless and amateur, that might better, through grasping the obscure and quiet reasons and guiding lights with no external concern other than to write, receive our general attention as not great marketing but great art. Like, for instance, Emily Dickinson, who couldn't be dragged out away from the house and her great understandings of all things, who wrote the immortal line, 'admiring bog.' (Of course, Joyce was 'published' through the help of Sylvia Beach, the ultimate generous art-house publisher patron.)

Joyce knew he was unpublishable in his great project. Fortunately Nora saved it from the fire. (One wonders, could he have come up with a more unpublishable book on so many levels and issues... Later, he tried actually.)

Having said my piece, I'll add, softly, that like Ulysses, and the hero himself, great art takes its own time. It would appear, perhaps, obsessive, foolish having nothing to do with the practical matters of worldly reality we human beings in society must live with and cope with. It has to include, perhaps softly at the edges, the great extent of the passing of time, 'a long time' in other words. (As Shane MacGowan observes in song.) And at the same time a sense of what time in the sense of moments to portray, is, that crazy thing, ever changing, ever slipping past us, ('bravely we beat on,' Fitzgerald wrote) that marvelous beautiful now we ever live in. How rich and rewarding life is, just as it is. That is all a great book needs to do. Like Keats' urn.

As an afterthought, a question: What has the digital age done to, or for, that moment of now? Our own now is peppered with now, other nows, but now qualified, sometimes real, as you can indeed share something real, even on facebook, with someone, but often muddled, overripe with illusory things of materialism, fame, with all the instant news we've developed a serious craving for, a lot of it pushing our own little real moments of now off to some exiled edge. Now gets corrupted, often enough, all too easily.

My sense is that if you were to wipe the slate clean from all the distractions, from all the diversions, you would find that the human being is an incredibly intelligent animal who is able to get some deep amazing stuff as far as thinking and considerations of what daily reality is. And you would find in the human the greatest faith in writing, just as Joyce must have had that unquestioning faith in writing as the thing to do.

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

A writer's thoughts

Okay, a wise young woman shared with me some observations after reading A Hero For Our Time. She recognized the element of insecurity in boy-girl relationships in the college setting. She pointed out a passage that captured a moment of insecurity (one way to read it), and what follows in the courtship dynamic, the attempt of reassurance, the thought, 'oh, I messed up the flow of things,' etc. College is a place where we first put ourselves on the line, and hopefully it goes well, when we say, 'here, this is who I really am, my dreams, my wants, my goals, my careful expectations.

In the face of insecurity, the question is, where do we find affirmation? Do we renounce our own powers to figure it all out by seeking affirmation outside of ourselves? Do we give all that power to another person, so that one's own self-image and self respect are tied to whether or not they accept us? Do we allow the steady relinquish and compromise of that which we would do pursuing our dreams and the utilizing of the talent we feel within?

Then the question, 'how have I fared in all of this?' Have I not challenged myself, wound up in some line of work that I am so hopelessly over-qualified for out of a psychology of failing to be accepted? Did the author, speaking through his main character, find a situation in which he sought out someone who would never accept him, thus finding a way to be lazy, 'well, I tried...' for the rest of his days? Does he personally hold on to that which is kryptonite to him, always reminding himself of imagined mistakes and shortcomings, as one might in a cyclical form of depression?

So, how have I fared? How has the author fared? What are his dreams, past, present and future? What were all those years of tending bar all about, the once bright young man now older with water under the bridge? Is it his dream to be the last one in a restaurant after all the waiters are gone night after night, as if he were some masochist, numbing the pains of tedium of the last few customers ('we're not keeping you, are we?') with a glass of wine, secretly desperate to escape?

Did he write a book as a way to gain that acceptance he once craved? Or rather was that effort about following the inner dream and then, somewhat bravely, putting it out there? While sometimes guilty of wishing otherwise of the nonacceptance, the author finds it a case of the latter, at the end of the day.

Perhaps it's not easy to go your own way. The same reader points out that here in the U.S. we are over-educated and therefore risk-averse, that we crave the beaten path, follow the checkpoints of societal acceptance, do not ruffle many feathers, make a decent buck and go on our merry way. Why should it be otherwise, but that perhaps some of us seek some form of innovation.

What do we want? What are our dreams? What holds us back?

It was an interesting sensation, this conversation mentioned above. That's why we write books, to shed light on matters that people don't immediately bring to discussion. Mind you, I don't mind, or rather welcome, a general remark upon the part of a reader, such as "yeah, I finished it," or, "solid effort," or some bare comment that leads to more silence, blankness. That is and will always be part of the authorial experience. And maybe for most on the time, oh, Jesus, you really don't want to go into the book you wrote (while you were and still are a barman), just too embarrassing, or just not an appropriate comfortable time and place to bring up such a thing. You didn't write a book for that external approbation, 'oh, that's good.' (Thus Ernest Hemingway's beautiful comment in the last vignette of A Moveable Feast concerning the praise offered to him by the rich, 'if the bastards liked it, I should have asked myself what the hell I was doing wrong.' not exactly quoted.) You wrote it to enter, if anyone pleases, the human conversation. You wrote it so that, if anyone might want, there could be a conversation, maybe an intelligent one about something. Like my father had made deeper comment about A Hero as an explication, a tale of 'a budding Theosophist,' in a letter. As a writer, remember, you don't always know, consciously (I guess is the word) what a book is about, which makes it art, for capturing things and thoughts and conversations at flora and fauna level, without saying interpretively, 'here's what it means,' in big letters; you just wrote it, guided by something, making no judgments, with few hopes, other than that the thing was/is somehow true, true to life, though it be a novel, or, if not a novel, at least a short story of long length.

So there it was, one early afternoon, as I had to think of getting ready, a little nervously, for work, a little kernal about insecurities, about putting yourself out there, early attempts of which, about the effects of lives beyond that, about that pernicious habit we always have going on in our heads to put meaning on something rather than just appreciatively living in the moment. Interesting.

The world from time to time gets sleepy, too involved with the news and worries, and ceases to believe in the notion of a great writer. Being a writer becomes to the world in general a question of who is published, and so it comes to be that a writer should be an expert in the field, someone at Harvard, a professional book churner of known name, a media celebrity. Which is to say that we don't recognize just anyone into the ranks, especially if you're not a 'someone.' No, we say to ourselves, we have to be scrupulous, time spent reading is money, it had better be for some sort of advancement. 'Someone as frivolous as a barman? No way, could never be a great writer. Just doesn't fit, you know, with the image. I mean, what's he got to say? How much tonic to put in?' And so the world goes round, ever needing a wake up call to what talents we, as a world of people, might possess, and the possibility for something to be said in a new or old way that works quite well.

I'm trying to get up in the mornings now. I'll get tired toward the end of the shift, but if it's possible, given the physical effort one must make in a night, it's probably worth it. Because it's all too easy to lose a grip on that important Circadian rhythm of daylight, all too easy to clasp a bottle of wine in your hand in hopes of calming down at the end of the night. I am a faulted person for having fallen into that trap so very often, that for too long, I'll admit, it became a habit, a norm. It is a good thing, along the lines of controlling such behavior, to write down one's goals. And so I try to get up and take a walk outdoors, to limber up, to get some daylight on me.

One of which should be GET THE HELL OUT OF THE RESTAURANT BUSINESS. Give yourself, what, a year? Six months? Three? Maybe not the sudden drastic change, but the pursuit of a goal, lining things up, instead of going, as it were, cold turkey. Why? Why is in necessary, this departure from a profession? I think largely because it erodes one's sense of self-esteem. Of course that isn't necessarily the case; one could perfectly maintain a fine sense of self-confidence, if working amidst restaurant and hospitality were one's life-long dream. But if you're like me, while you'll find the flow of people and personalities interesting, while you might find your co-workers interesting and honorable, you'll find that your dream is a bit different. Maybe you can find amelioration, accept that you yourself bring a certain theater to the serving end of things. After all, hospitality is entertainment. And of course, that involves acting, a worthy enough profession, I suppose.

Restaurant's may well work through harnessing a basic decency, something inherited and learned from parents. Regular guests enjoy the cultural conversation you have to offer. You work hard because your co-workers are working hard. A basic politeness rules an establishment, occasionally stressed, but always underlying. But, politeness can have the effect of sucking you into a cult, as perhaps there is something of that to the lives of those who work at night. When done with what work (the cult) demands of them, they unwind perhaps with like 'lost souls,' then go home alone after everyone else has gone to bed, too tired to do much more than watch a flickering TV screen. Restaurant people, oddly enough, are self-disciplined.

Did the restaurant initially seem like a refuge for creative types? Was it that it let you with days free, back when you were working on something of a piece of writing? Was it that the office life just struck you as so grossly unnatural (and hard on the spine) that you couldn't make the initial investment in it? Was it the thirst for something not boring, or the adrenaline rush? Did you think the restaurant business would allow you a better freedom to exercise?

And so you toiled away, sort of half-assed, but getting the job done. Years went by. You trusted. You pursued your stuff on the side, as best you could, hey, to your credit. You have to hand it to the bravery of the effort and its patient steadfastness. But, where did it get you? How much were you able to save? A retirement plan? Not that you were spending money on more than the basics.

To make enough money to get by, you lose an amount of your will, an amount of your pride. It is a physical challenge, not so much an intellectual one. The passing stranger has the reaction of wondering what someone of your intelligence in doing in such a job, and sometimes sense your frustration. Or, easier, they won't attribute to you (in your professional quietness) the quality of intelligence and knowledge of matters in general. And on the working end of it, you hopefully remember, and look forward to the times when there was an intelligent conversation you were engaged in, maybe one that called up some part of hidden skill that people did not expect of you, and remember, on some gut level, the brightness and engaging quality of the guy you tip for the service he provides, twenty percent or so. An odd bird, perhaps.

Murakami, he worked in his jazz bar. And then he got published, and then he changed his life, and became a great writer.

In the face of insecurity, the question is, where do we find affirmation? Do we renounce our own powers to figure it all out by seeking affirmation outside of ourselves? Do we give all that power to another person, so that one's own self-image and self respect are tied to whether or not they accept us? Do we allow the steady relinquish and compromise of that which we would do pursuing our dreams and the utilizing of the talent we feel within?

Then the question, 'how have I fared in all of this?' Have I not challenged myself, wound up in some line of work that I am so hopelessly over-qualified for out of a psychology of failing to be accepted? Did the author, speaking through his main character, find a situation in which he sought out someone who would never accept him, thus finding a way to be lazy, 'well, I tried...' for the rest of his days? Does he personally hold on to that which is kryptonite to him, always reminding himself of imagined mistakes and shortcomings, as one might in a cyclical form of depression?

So, how have I fared? How has the author fared? What are his dreams, past, present and future? What were all those years of tending bar all about, the once bright young man now older with water under the bridge? Is it his dream to be the last one in a restaurant after all the waiters are gone night after night, as if he were some masochist, numbing the pains of tedium of the last few customers ('we're not keeping you, are we?') with a glass of wine, secretly desperate to escape?

Did he write a book as a way to gain that acceptance he once craved? Or rather was that effort about following the inner dream and then, somewhat bravely, putting it out there? While sometimes guilty of wishing otherwise of the nonacceptance, the author finds it a case of the latter, at the end of the day.

Perhaps it's not easy to go your own way. The same reader points out that here in the U.S. we are over-educated and therefore risk-averse, that we crave the beaten path, follow the checkpoints of societal acceptance, do not ruffle many feathers, make a decent buck and go on our merry way. Why should it be otherwise, but that perhaps some of us seek some form of innovation.

What do we want? What are our dreams? What holds us back?

It was an interesting sensation, this conversation mentioned above. That's why we write books, to shed light on matters that people don't immediately bring to discussion. Mind you, I don't mind, or rather welcome, a general remark upon the part of a reader, such as "yeah, I finished it," or, "solid effort," or some bare comment that leads to more silence, blankness. That is and will always be part of the authorial experience. And maybe for most on the time, oh, Jesus, you really don't want to go into the book you wrote (while you were and still are a barman), just too embarrassing, or just not an appropriate comfortable time and place to bring up such a thing. You didn't write a book for that external approbation, 'oh, that's good.' (Thus Ernest Hemingway's beautiful comment in the last vignette of A Moveable Feast concerning the praise offered to him by the rich, 'if the bastards liked it, I should have asked myself what the hell I was doing wrong.' not exactly quoted.) You wrote it to enter, if anyone pleases, the human conversation. You wrote it so that, if anyone might want, there could be a conversation, maybe an intelligent one about something. Like my father had made deeper comment about A Hero as an explication, a tale of 'a budding Theosophist,' in a letter. As a writer, remember, you don't always know, consciously (I guess is the word) what a book is about, which makes it art, for capturing things and thoughts and conversations at flora and fauna level, without saying interpretively, 'here's what it means,' in big letters; you just wrote it, guided by something, making no judgments, with few hopes, other than that the thing was/is somehow true, true to life, though it be a novel, or, if not a novel, at least a short story of long length.

So there it was, one early afternoon, as I had to think of getting ready, a little nervously, for work, a little kernal about insecurities, about putting yourself out there, early attempts of which, about the effects of lives beyond that, about that pernicious habit we always have going on in our heads to put meaning on something rather than just appreciatively living in the moment. Interesting.

The world from time to time gets sleepy, too involved with the news and worries, and ceases to believe in the notion of a great writer. Being a writer becomes to the world in general a question of who is published, and so it comes to be that a writer should be an expert in the field, someone at Harvard, a professional book churner of known name, a media celebrity. Which is to say that we don't recognize just anyone into the ranks, especially if you're not a 'someone.' No, we say to ourselves, we have to be scrupulous, time spent reading is money, it had better be for some sort of advancement. 'Someone as frivolous as a barman? No way, could never be a great writer. Just doesn't fit, you know, with the image. I mean, what's he got to say? How much tonic to put in?' And so the world goes round, ever needing a wake up call to what talents we, as a world of people, might possess, and the possibility for something to be said in a new or old way that works quite well.

I'm trying to get up in the mornings now. I'll get tired toward the end of the shift, but if it's possible, given the physical effort one must make in a night, it's probably worth it. Because it's all too easy to lose a grip on that important Circadian rhythm of daylight, all too easy to clasp a bottle of wine in your hand in hopes of calming down at the end of the night. I am a faulted person for having fallen into that trap so very often, that for too long, I'll admit, it became a habit, a norm. It is a good thing, along the lines of controlling such behavior, to write down one's goals. And so I try to get up and take a walk outdoors, to limber up, to get some daylight on me.